This article is intended for readers with a technical background. Basic knowledge of IT and server administration (Linux) is recommended.

TL;DR

This is our tech-stack:

- hosting: Hetzner Cloud

- services: AWS S3 and SES, Hetzner VPN, load balancing, block storage, and managed SSL certificates, Stripe for payments

- programming languages: Go (golang), TypeScript

- software: Docker, HashiStack (Consul + Nomad + Vault) for container orchestration, Traefik for routing, GoLand and Visual Studio Code for development

When it comes to building and hosting a SaaS, you will basically hear about two approaches. The first is to use the services of a (large) cloud provider, such as AWS, Azure or Google Cloud. This approach is usually chosen by startups that have funding or already have experience using these services. The second option is to host it yourself, usually on dedicated servers or virtual machines. This lean approach is good if you want to keep it simple and get started quickly and inexpensively.

I think we fall in between these two approaches, neither do we spend too much on cloud services/servers, nor do we have a simple setup. That’s why I think it’s worth telling you more about how we run Pirsch. In this article you will learn how we develop Pirsch, what hardware and software we use and why we chose the technology we did.

Hosting

Starting with hosting, we use virtual machines on the Hetzner Cloud based in Falkenstein, Germany, running Ubuntu Linux. The main reason we chose Hetzner is the cost. A single-core VM on Google Cloud starts at about $31/month (in Frankfurt), while a single-core VM on Hetzner costs about 2.50 €/month. Pirsch runs on a three-node cluster, plus an additional VM for the database, all configured with two cores and 4 GB RAM. We previously had a similar setup for Emvi on Google Cloud, which cost about 250 €/month, while we currently pay about 45 €/month for everything (including cloud services).

Why not use dedicated servers, you may ask. It makes sense from a cost-benefit perspective, but dedicated servers are less flexible. Renting a dedicated server is more of a commitment than setting up a VM that you can stop or rescale at any time. If the need arises, we can scale the VMs vertically or add dedicated servers later. Flexibility is one of the main reasons cloud services became so popular, but it comes at a price. Hetzner offers a good balance between flexibility and cost.

Services

There are a number of (cloud) services that we use.

Storage

We are using two types of storage at the moment. The first is block storage (aka “volumes”) on Hetzner for the Postgres database. The ClickHouse instance uses the VM’s hard disk. Both are replicated automatically, so you don’t have to worry about data loss. The second is AWS S3 for user images and email reports. We use an external object store, so that we can serve images from any cluster node. The S3 API is basically an industry standard now. So if needed, we can switch to an alternative or self-hosted variant.

AWS SES (Simple Email Service) is our email service of choice. The main reason why you shouldn’t host your own mail server is that mail servers are a nightmare to maintain, and we don’t want to deal with that. We previously used SendGrid, but that costs $15/month for 40,000 emails, while SES only costs 10 cents for 1,000 emails (so $4 for the same amount as SendGrid) and we don’t need any of the other SendGrid features. We typically send less than 1,000 emails per month, and we haven’t paid anything for SES yet (I think it’s free up to a certain amount of emails, or they just don’t invoice for pennies). The emails are always rendered in our backend using Go templates. The newsletter is sent manually for now.

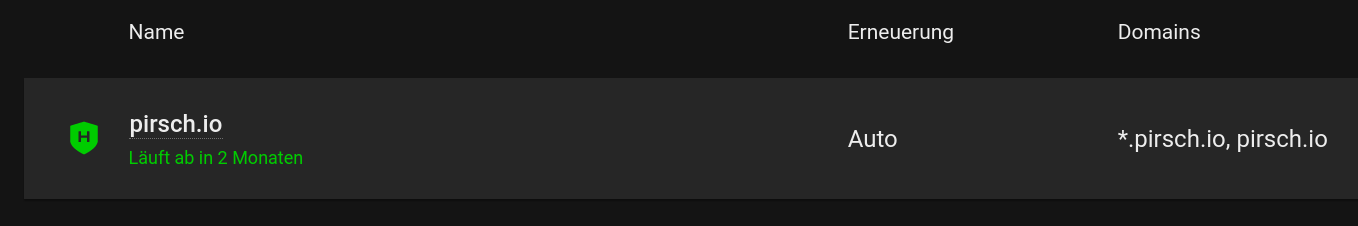

SSL Certificates and Networking

SSL is something I have struggled with a lot. While Letsencrypt is a great service that I really appreciate, there are a million ways to issue and place certificates on your servers. I was never quite sure which one to use. We had our own acme-dns server that seemed to work, but then clashed with a DNS service that was running on port 53. We used Traefik’s built-in system to issue certificates, built our own service to update the load-balancer certificate on Hetzner, and so on. In the end, Hetzner released an update so that the load balancer can use a fully managed (wildcard) certificate. You just need to use Hetzner’s DNS servers and it will be updated automatically.

In addition to the load balancer, we also use a firewall and a private network for the cluster and the database servers. All built directly into the Hetzner cloud. To route traffic to the desired service, we use Traefik. For example, if you visit pirsch.io, your request will be routed to the website service. Everything on *.pirsch.io is routed to the dashboard, and so on. You can see a sample configuration below the deployment section.

Subscriptions and Payments

Subscriptions and payments are managed and processed by Stripe. We have used Stripe before and continue to use it for Pirsch. The API and dashboard are fantastic, and they have a great Go SDK.

Programming Languages

If you follow our development on GitHub or Twitter, you probably already know that we use Go (golang) for backend and TypeScript for frontend development. I don’t want to go into too much detail here, as there are other articles that better explain the pros and cons of these languages.

Go is a fantastic language with good performance characteristics because it is statically typed and compiled to machine code. The simplicity helps to keep Pirsch maintainable and extensible, and we like that it’s made for the web. Our website for example is rendered using Go templates.

TypeScript is something we just recently switched to, coming from vanilla JavaScript (ES6). It’s a good fit for Vue 3 applications, which we use to build our dashboard. I was skeptical about TypeScript, because I didn’t really see the need for types in a scripting language. But as complexity grows, it really helps to maintain the app. You can read more about this on my personal blog.

Development

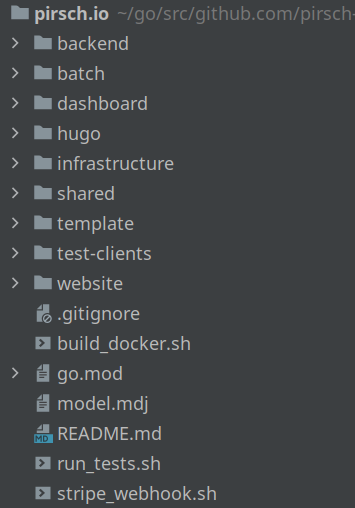

Something we really appreciate is that we can build, test and run Pirsch locally. For this reason, all parts of the application (backend, website, dashboard, batches and databases) can be launched without first building the Docker images or changing the YAML configuration. Only the databases (Postgres and ClickHouse) are run on our machines via Docker. This allows us to quickly iterate, test new features, and experiment. We also generate a test dataset at startup, so we have something to look at when we open the dashboard.

All parts of the application can be started with a simple go run main.go or npm run watch (for the dashboard) command in their respective directory. This is how the directory structure of the project looks like.

If you look closely, you will notice that we have a script run_tests.sh. This is used to run all Go and TypeScript tests locally. Since we are a two-person company, we haven’t bothered to set up CI (yet). Before each commit or release, we run the script to make sure the tests are successful. This is probably not the way you should do it (you might forget to run it) and clearly a lazy solution, but the tests only take a few minutes and are usually cached, so usually only take a few seconds.

Before we do a release, we create the Docker images locally and push them to the GitHub container registry (all code is managed on GitHub).

The HashiStack, Databases, and Deployment

This section has been the most requested by our users and followers. I won’t be able to explain every detail of our setup, but I want to highlight why you should consider our choice in favor of other container orchestrators like Kubernetes.

Consul, Vault, and Nomad

When people talk about the HashiStack, they mean the combination of Consul, Vault, and Nomad developed by HashiCorp. These three pieces of software together form the server cluster for Pirsch. There is a free open source version for each of them and an enterprise tier for larger organizations and multi-cloud clusters. HashiCorp also offers managed solutions in case you don’t want to maintain it yourself.

Consul is used for server meshing and service discovery. It provides a DNS interface to resolve hostnames (like my.service.consul) to IP addresses. Vault securely stores secrets and allows access to them from Nomad. It’s a very powerful tool that offers much more than that, but we’re only using it to manage secrets and passwords at the moment. Nomad is a container orchestrator used for scheduling containers and batch workloads (more on this in the deployment section).

Taken together, Consul, Vault, and Nomad can be considered lightweight alternatives to Kubernetes. Lightweight because they are easy to set up and maintain, which makes them a good solution for small businesses that want to maintain their own cluster. The HashiCorp configuration language (HCL) is a big improvement over Kubernetes’ YAML files, and there are far fewer concepts to learn. Each part of the stack has its own focus and can be installed independently, but they integrate very well. Nomad, for example, automatically discovers other nodes during installation with the help of Consul.

Another reason to choose HashiStack over its alternatives is the documentation. HashiCorp’s documentation pages are very well written, beautiful, and most importantly, complete. You can set up the stack by following the instructions without missing anything important. Something I really dislike about documentation is when it skips steps because they are “too complicated” at that point. HashiCorp doesn’t make those cuts and explains everything you need to set up a production-ready cluster. You don’t have to spend countless hours trying to figure out how to secure the cluster or troubleshoot because something is missing from the documentation.

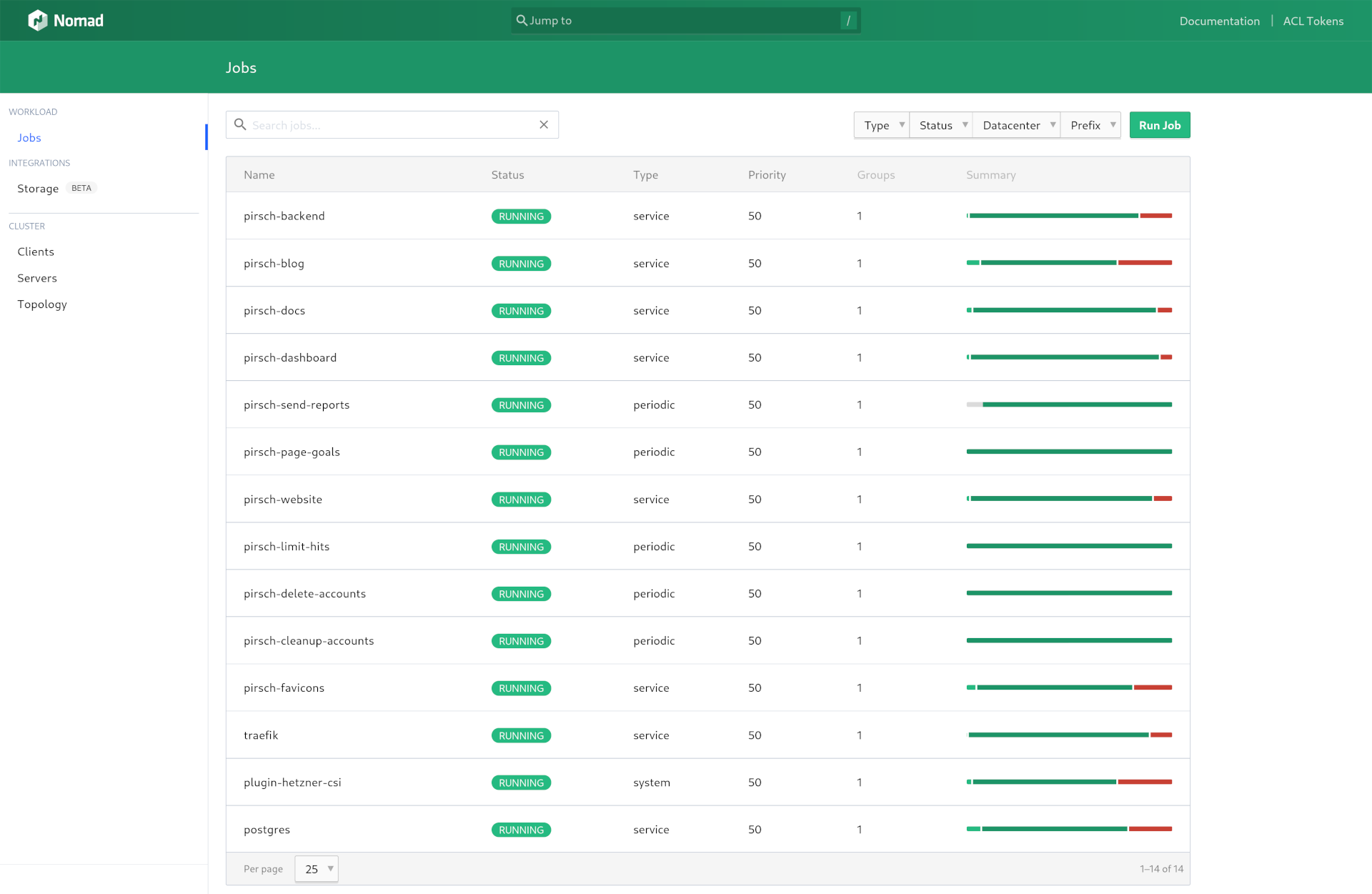

Last but not least, all HashiStack tools have nice web UIs that make it really easy to deploy your software, discover problems, view log files, and much more.

The only thing that caused some confusion when setting up the stack was that Consul’s service discovery did not work on our Ubuntu servers at first. The problem was that the DNS service conflicted with systemd-resolved on port 53. The solution was to let systemd-resolved listen to Consul’s DNS service. This can be configured by editing

/etc/systemd/resolved.confand changing the following lines.> DNS=127.0.0.1 > Domains=~consul > ``` > > We also had to add these two iptable rules... > > ``` > iptables -t nat \ > -A OUTPUT -d localhost \ > -p udp -m udp --dport 53 \ > -j REDIRECT --to-ports 8600 > iptables -t nat \ > -A OUTPUT -d localhost \ > -p tcp -m tcp --dport 53 \ > -j REDIRECT --to-ports 8600 > ``` > > ... and add this to the anonymous policy for the Consul token: > > ``` > service_prefix "" { > policy = "read" > } > > node_prefix "" { > policy = "read" > } > ``` ### Databases Pirsch uses two databases, Postgres and [ClickHouse](https://clickhouse.tech/). You have probably heard of Postgres before. We use it to store user account data and configuration. It is part of the server cluster because it is not heavily loaded and therefore does not need its own server. However, you may not have heard of ClickHouse. It is an analytical OLAP database developed by Yandax. The main difference with generalized databases like Postgres is that it stores data in a time series on disk. This allows data to be quickly searched and aggregated based on time ranges. We chose it because it fits our needs perfectly and is very well supported on GitHub. It is installed on its own server because it can get very power-hungry and we want to keep response times low. At the moment it only uses a small virtual machine with two cores and 4 GB of RAM, but we can always scale it up. ### Deployment Deploying a new version for any part of the application is simple. We update our Nomad job configuration, schedule the change on the web UI, and execute the deployment. This is the main reason we run a server cluster. The workload could currently be met by a single server, but we couldn't do zero-downtime deployments. Also, when we upgrade the system, something might break, causing downtime. A three-node cluster helps with that because the servers can be updated one at a time, ensuring that the entire system stays online. Here is an excerpt from our backend job file. ```YAML job "pirsch-backend" { datacenters = ["fsn1"] # fsn1 is Falkenstein type = "service" group "pirsch-backend" { count = 3 update { max_parallel = 1 # ... } network { # port } task "backend" { driver = "docker" config { # Docker image, ports, volumes, ... } # YAML configuration file as part of the job file template { data = <<EOF version: "1.6.4" logging: level: info # ... EOF } } service { name = "backend" port = "backend" # the Traefik configuration to route traffic to the service tags = [ "traefik.enable=true", "traefik.port=9999", "traefik.http.routers.backend.priority=40", "traefik.http.routers.backend.rule=Host(`api.pirsch.io`)", "traefik.http.routers.backend.entrypoints=http", ] check { # health check } } } }

Usually, we just update the version number or make some changes to the embedded YAML configuration to deploy a new version. It will then pull the Docker image from GitHub and spin up the service, gradually replacing the currently deployed version. Here is a screenshot of all the jobs we are currently running on Nomad.

Batches and the system services (Traefik, Hetzner CSI plugin, and Postgres) are deployed in a similar way.

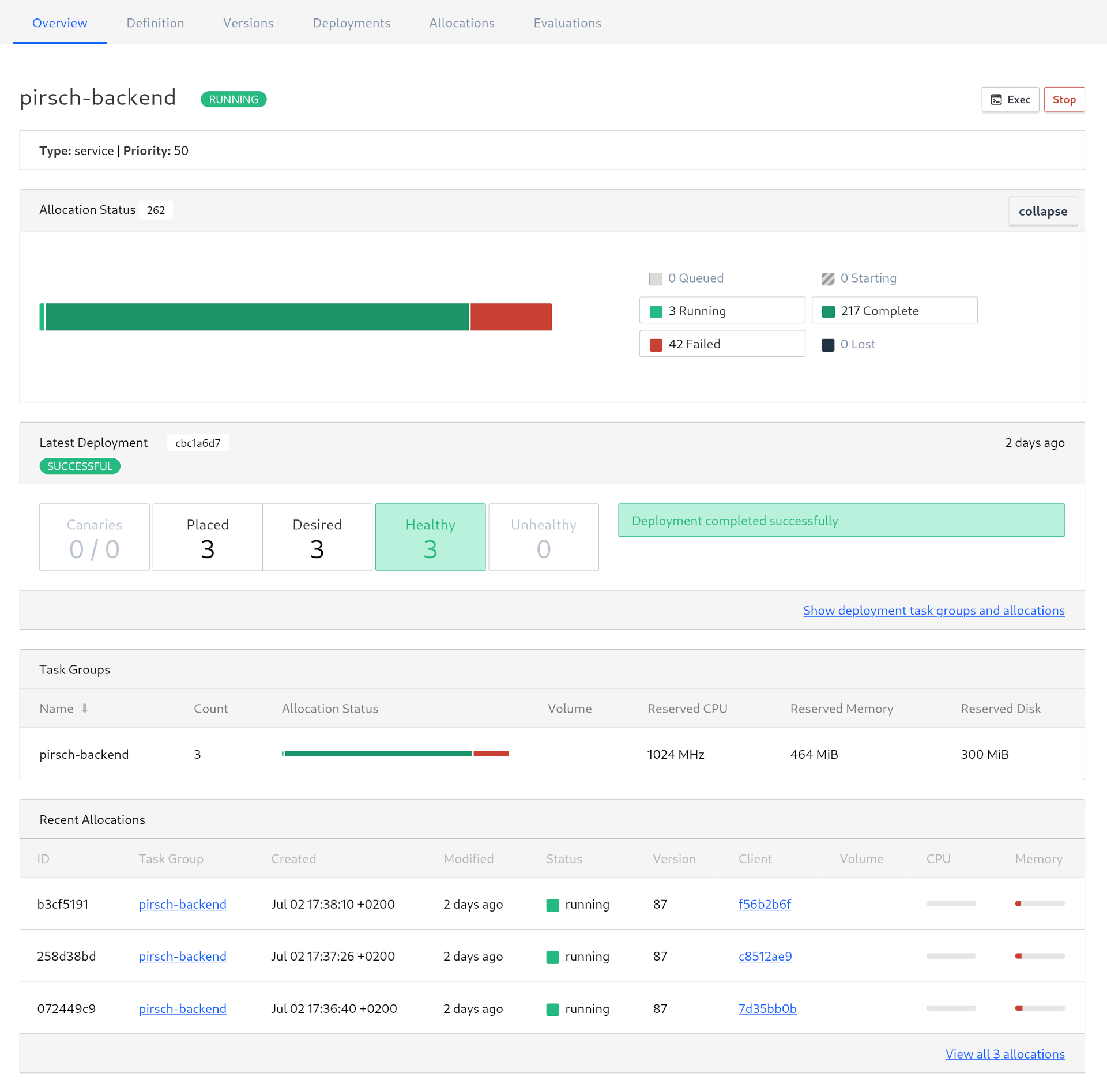

Here is a screenshot of the deployed backend job.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed learning more about how we develop and run Pirsch. If you want to know more or have specific questions about our setup, please feel free to contact us on Twitter @PirschAnalytics or send us an email.

Title image by Adi Goldstein